What’s left to look

Shhh: Southern high hidden histories

Alessia Rollo

I can already see that herd of men and women starting to roll towards the south, among its dusty streets, in the sultry heat. The air is suspended, time is still. They have their eyes fixed on the people they meet on the street and they fix them back. Perhaps out of habit or perhaps out of amazement. They laboriously drag their equipment, scan the horizons waiting for something to move in a South without borders and limits.

Slowly they slip into houses, fields, squares, and churches. They wait, they examine. Here they are finally entranced when something happens, the invisible possesses bodies, places and scenes.

The flashes light up, the cameras shoot, the microphones record.

The rite begins and dies at that moment.

When a group of anthropologists, ethnographers reveal reality, they tear the veil of enchantment apart and clarify everything. The camera explains the world and minds of the Southern Italy people unravelling their deceptions before their eyes.

Thus, we leave Plato’s cave to enter the camera lucida. We abandon our social structures, its topos and logos. For many decades we’ve been also ashamed of it, remembering with nervous smiles of when we lit pyres for the saints and taranta (the wolf spider) bites brought possession. We stop ped greeting the sun, celebrating solstices and seasons.

The squares are emptied, miracles no longer happen, and ritual ceremonies vanish. Just as photographers and directors disappear. Everything is explained, there is nothing more to look at.

“[…] rites, ceremonies, social and natural relationships are looked at, analysed and photographed coldly to be catalogued according to a positivist mentality that needed the camera”

It is no coincidence that Ernesto De Martino, perhaps the most famous anthropologist of the past century, was accompanied on his scientific expeditions in Southern Italy by the eye of a camera, applauded since its birth for its extraordinary quality: having a high indexicality sign, that is, always pointing out something true, something that was really in front of the camera lens.

Camera and reality seem to fit together. Therefore, by syllogism also camera and truth.

It so happens that decades of images, sounds, videos made since the 50s on Southern Italy build a very compact index on the archaicity, exoticism and primitivism of the civilizations that were about to remain outside the technological progress that instead had widely taken hold in Northern Italy.

And therefore rites, ceremonies, social and natural relationships are looked at, analysed and photographed coldly to be catalogued according to a positivist mentality that needed the camera, daughter of progress and technological faith, to generate documents of reality useful for refuting the anthropological claims’ truth.

“But something has escaped the photographic eye that explained the world as a speech, while ritual life is quite the opposite: signifiers without meanings, a universe of symbols.”

But something has escaped the photographic eye that explained the world as a speech, while ritual life is quite the opposite: signifiers without meanings, a universe of symbols.

In his “The Disappearance of Rituals” Byung Chul Han explains that the rites and ceremonies are genuine human actions capable of making life appear in a festive and magical key, while their disappearance desecrates and profanes, making it mere survival… “

Today, after 70 years, it is perhaps permissible to ask what the role of visual anthropology in the construction of the historical-social image of Southern Italy was.

This personal reflection was generated by the awareness of the historical thought of the time, by its need to eradicate the rural model of the south, the consequent construction of the “southern question” and the absence of photographers from Southern Italy in the representation of this geographic area.

But it also comes from irritation and from an image: or from irritation in an image.

In 1962, Gianfranco Mingozzi made the famous documentary “La tarántula”. The long sequence of scenes shot in the Salento countryside and the narrator tears the eye with the desolation, abandonment and cruelty of the landscape and life of those places’ inhabitants. Salento is visually a mix between a western movie by Sergio Leone and a Maya Daren’s documentary on the voodoo rituals of Haiti.

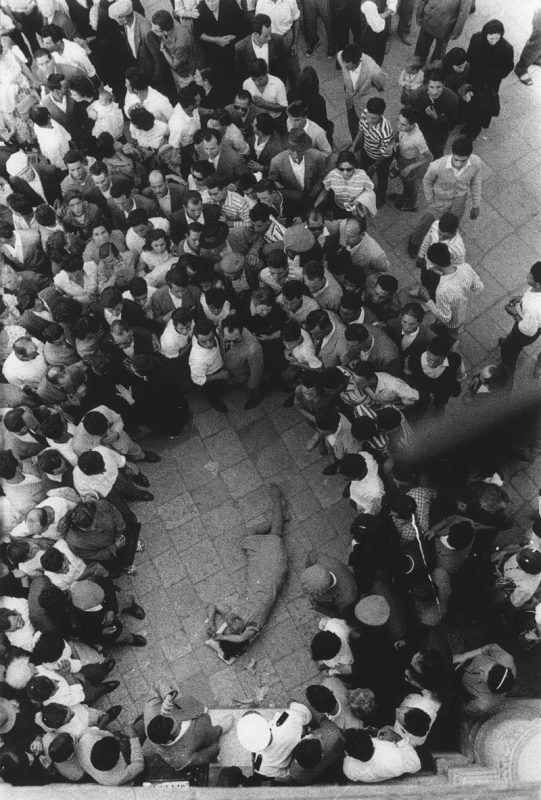

Mingozzi and his crew then arrive in the small villages where the camera lingers in different houses, tells the pain, emphasizes the evil, the boredom, the people’s broken dreams to finally arrive in front of the square of the San Pietro and Paolo’s small chapel in Galatina, pilgrimage destination of the tarantata women.

This is where a double track disclosure takes place.

The camera is probably fixed on the balcony in front of the church entrance, to create what was defined by the photographers and filmmakers of the time as a “surprise effect”: a technique that ensured a neutral documentation of the scene without the observed subjects being able to modify their own behaviours due to the presence of a camera.

The first revelation therefore is the one desired by the director towards the viewer of the movie, to know the reality of the facts thanks to the revelations of the camera.

Let’s go back to the scene. The room frames a small group of people, including a middle-aged woman who begins her dance-cathartic rite by hopping back and forth towards the entrance to the chapel. The woman suddenly looks up and sees the camera, goes back and addresses the cameramen with an irrefutable “Anculu a mammata” (ed. “Fuck your mother”).

Here is the second disclosure. The camera ripped open the veil, violated the rite and scorned the faith.

That woman knows it, she fully understood that the rite dies because it is explained to the eyes and to the outsiders.

As in other images by Chiara Samugheo and Franco Pinna, furious glances turn to the cameras of the photographers who try to document all frantically.

“The ritual magical world is visually absent: it is impossible for the viewer to understand what he observes, since he hears nothing and sees too much. Like eros that turns into pornography when everything is clear and nothing remains to the imagination.”

These photographs, certainly of great aesthetic power, have been used as historical and informative documents for decades.

But what do they demonstrate and what exactly are they pointing to?

Leafing through books, magazines or watching the videos, what is missing is exactly what the machines are pointing to.

Where is the magic, the enchantment that should have populated bodies, places, and scenes?

The ritual magical world is visually absent: it is impossible for the viewer to understand what he observes, since he hears nothing and sees too much. Like eros that turns into pornography when everything is clear and nothing remains to the imagination.

So, what was there to look at?

In an era in which the dominant models of thought are being dismantled and in which cultural diversity is celebrated, new visual narratives should be encouraged in and about Southern Italy that can reintegrate the representations of the past and enrich them through a “re-enchantment of the world”.

If a part of the South’s social life has been flattened by a positivist rationalism that didn’t manage to convey the overall nature of a system and its cultural manifestations, much remains to be seen in terms of contents and forms, hoping that in the future we will look at visual self-representations with more attention and leave more space for them in this strip of land.